The bond between the creator of beloved boy reporter Tintin and a prominent Chinese artist was a meeting of great minds.

Born in 1907 and raised in a Jesuit orphanage in Old Shanghai, artist Zhang Chongren would become one of the greatest sculptors of his era, being called the “the Rodin of the East”.

In the mid-1980s, French cultural authorities even made a cast of his hands, an honour previously bestowed only on Auguste Rodin – considered the founder of modern sculpture – himself, and painter Pablo Picasso.

But what really made Zhang the most famous Chinese person in Europe for much of the 20th century was his remarkable relationship with Georges Remi, creator of the beloved 24-volume comic strip The Adventures of Tintin, now translated into more than 70 languages, with a readership approaching a billion.

By the time Remi, known professionally as Hergé, first met Zhang, in May 1934, Tintin was enormously popular. What had started in 1929 as a roughly drawn comic strip featuring a crusading boy journalist who did not do much journalism, published in the conservative, sometimes fascist-friendly, Catholic Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, had evolved into a fully fledged French-language phenomenon.

Toddler Zhang Chongren at the knee of his silk embroiderer mother. Illustration: Samuel Porteous

However, for all the success of the four Tintin books published until then, in the opinion of most tintinologists Hergé had yet to produce his first true masterpiece.

That would be The Blue Lotus (1935), which took the globe-trotting Tintin to China, where the heroic boy-reporter battles an international opium-smuggling ring in an Old Shanghai upended by the Sino-Japanese conflict of the 1930s.

In French newspaper Le Monde’s 1999 list of the most important literary works of the 20th century, The Blue Lotus ranked 18th, below In Search of Lost Time (1913), by Marcel Proust, but ahead of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1920). The French take comics/graphic novels, what they call “the Ninth Art”, very seriously.

Not only would Zhang serve as inspiration for a main character in The Blue Lotus – plucky orphan Chang Chong-chen – he would also play a crucial role in the development of its art and storyline.

As set out by Hergé biographers such as Pierre Assouline and Benoit Peeters, the epochal meeting between the two men was no product of chance.

In March 1934, when Hergé hinted that Tintin’s next adventure might take him to China, a network of progressive Catholic priests eager to improve Chinese relations with the West and the Church was alarmed and excited.

Key members of this group included Father Leon Gosset, a young chaplain for Chinese students studying in Europe, China specialist Father Édouard Neut, author of several treatises on the country, and “Dom Celestin”, née Lu Zhengxiang, a former Republican-era Chinese prime minister who became a Bruges-based Benedictine monk.

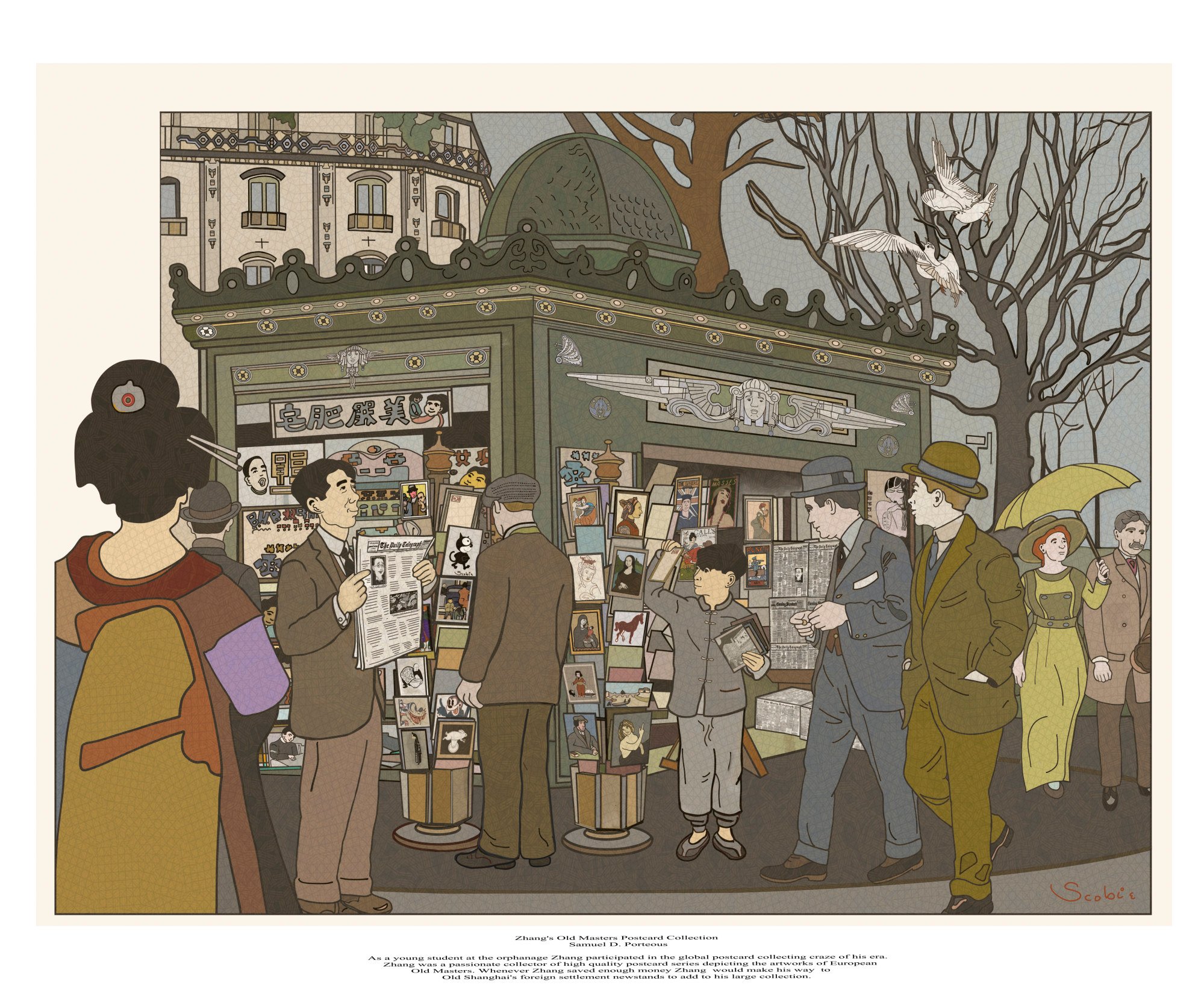

Zhang at around the age of eight-12 took part in the global postcard collection craze of that era. This also allowed him to get an education in the European Old Masters. Illustration: Samuel Porteous

The group hoped for a Tintin storyline that would show support for a China besieged by Japanese imperialism, a situation to which Europe was – at best – indifferent.

They also wanted to avoid stereotypes that marred some of Hergé’s previous efforts such as Tintin in the Congo (1931), wherein Africans were depicted as slow-witted, childlike and in need of Belgian guidance.

Hergé’s track record in depicting Chinese characters offered little encouragement. In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929), Tintin’s first adventure, two cruel and crudely depicted Chinese, complete with queue hairstyles and exaggerated features, are hired to torture Tintin.

In the third volume, Tintin in America (1932), two oriental thugs try to eat the boy’s beloved dog, Snowy.

The group felt the best way to avoid such gaffes would be for the well-meaning but still young Hergé to meet actual Chinese studying in Belgium, who could teach him about Chinese culture and politics.

Father Gosset, a Tintin fan, reached out to Hergé and laid out the group’s concerns and their proposal. Hergé agreed and Father Lu knew exactly who he should meet.

Lu had met Zhang when the artist first arrived in Europe in 1931, on a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship at the Belgian Academy of Fine Arts, and as a highly recommended protégé of famed Chinese educator and fellow Catholic Ma Xiangbo.

It was Ma, a co-founder of Fudan University in Shanghai, whose philanthropy had enabled the creation of the Tushanwan Orphanage from which Zhang graduated.

Patriotic Zhang needed little convincing to participate in the effort. And so the two artists, both born in 1907, met on May 1, 1934, and hit it off immediately.

The diminutive Zhang felt such an affinity for Hergé that he believed they had met in a previous life. The lanky Hergé, true to his scouting nickname Curious Fox, sensed something exceptional about Zhang.

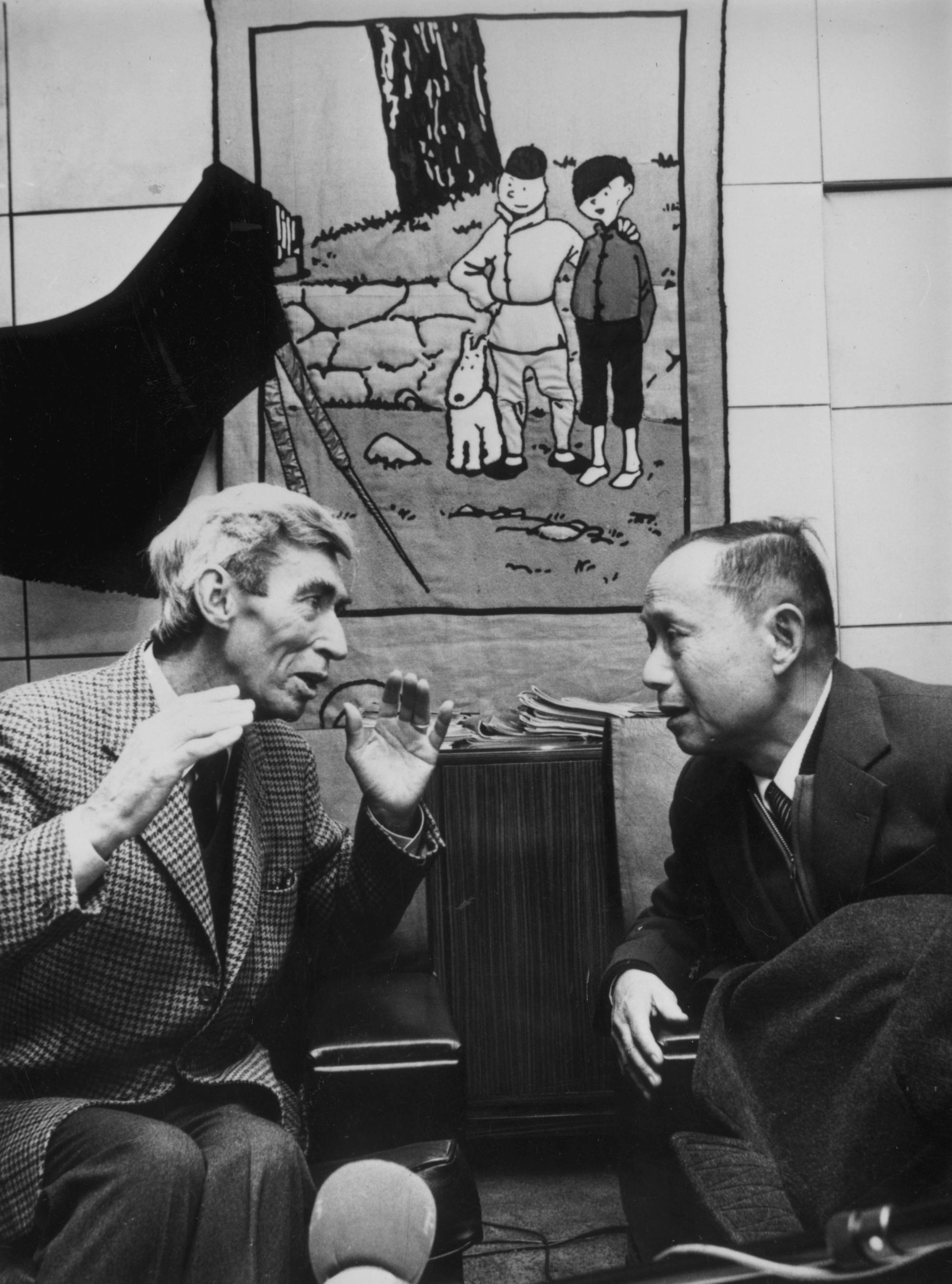

Belgian cartoonist Hergé (left) and Zhang at the Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels in the 1930s. Photo: Getty Images

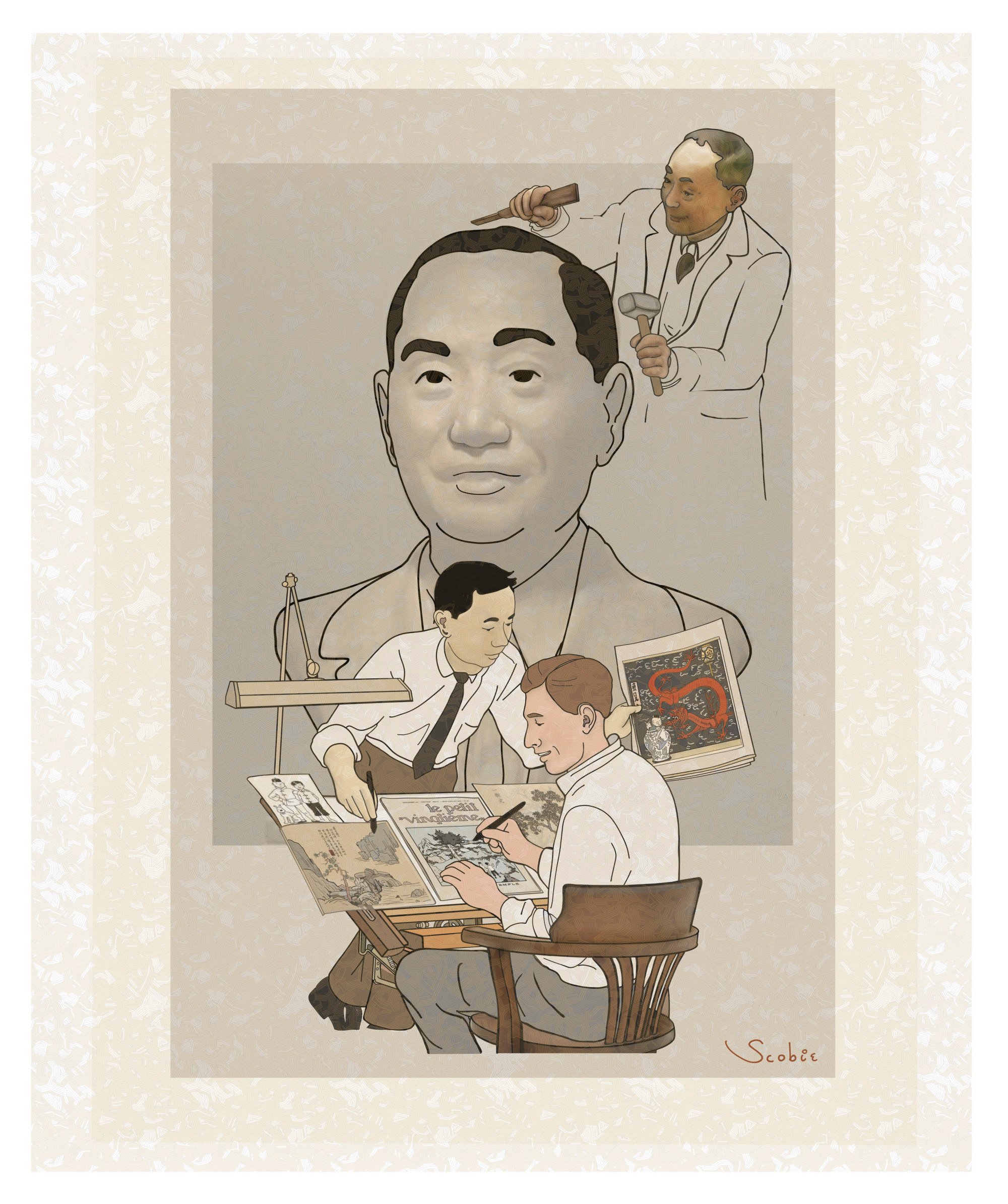

Over the next year, Hergé and Zhang would meet almost every Sunday afternoon at the town house Hergé shared with his wife, Germaine, where Zhang introduced him to the basics of Chinese painting.

They discussed the nuances of Chinese philosophy, culture and politics, including China’s struggles with Western settlements and Japanese aggression: themes that would inform the storyline of The Blue Lotus.

According to Zhang, the two would also sometimes travel to the Bruges Abbey for long talks on these subjects with Father Lu. It was during these discussions that Hergé decided to portray the infamous Mukden Incident of 1931, wherein Japan staged an attack on a railway as pretext for the occupation of Manchuria.

Hergé came up with the idea of Tintin coming upon the Japanese saboteurs as they did the deed.

And after engagement in politics, came the question of the art itself. Zhang gave Hergé a set of Chinese paint brushes and a treasured copy of The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting.

Used by Chinese art students since 1679, the book was a collection of hundreds of illustrations of plants, animals and landscapes at various stages of completion complete with commentary.

The manual, with its focus on the width and fluidity of an artist’s lines, had a significant impact on what became Hergé’s renowned ligne claire, or clear line, a style that influenced both Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

Their art discussions were not merely technical. One Sunday afternoon Zhang introduced Hergé to the Taoist fashion in which to observe a small tree in his garden. Years later, Hergé wrote of how the nascent master sculptor had stood before this heretofore unremarkable plant and explained its life to him, how its struggles had been captured in its form.

“You helped me see its first surge towards life, its enthusiasm, and then its first disappointment, the courage and perseverance it displayed which had helped it to overcome those weaknesses.”

Hergé, the autodidact who walked out of the one art class he attended, listened to Zhang’s spontaneous discourse, in Hergé’s own words, “spellbound”. From that point on Taoist philosophy became an important part of both Hergé’s art and life.

The three ages of Zhang: a) young man working with Hergé, b) middle aged, c) elderly Zhang, and d) their avatars Tintin and Chang on the desk. Illustration: Samuel Porteous

As they set to work producing the book, Zhang also helped with the more prosaic details such as ensuring the Chinese clothing and buildings portrayed in the book were accurate and took responsibility for inking the myriad Chinese characters displayed in the signs and banners throughout the story.

Zhang used these elements, with Hergé’s knowledge and blessing, as an outlet to express his own anti-imperialist sentiments. “Down With the Unfair Treaties!” was just one example.

Hergé even offered Zhang co-authorship, something he would never do again for any other collaborator. Zhang declined, but during his artistic assistance, Zhang did playfully insert his Hanzi name into artwork throughout the book.

Tintin experts such as Belgian writer and Artcurial Paris consultant Marcel Wilmet speak of clear “Before Zhang” and “After Zhang” eras in Hergé’s oeuvre, marked by a notable maturation in Hergé’s art as well as a new sense of responsibility to give readers accurate depictions of the people and countries portrayed.

In late 1935, Zhang graduated from the Belgian Academy of Fine Arts with many honours, turning down a professorship and accompanying studio when he learned it necessitated taking Belgian citizenship.

Diploma in hand, Zhang returned to Shanghai, and would not witness the full success of the China-friendly, fifth volume of Tintin, The Blue Lotus. It was a success that engendered both official protests from the Japanese government, and an invitation to Hergé from a grateful Madame Chiang Kai-shek to visit China.

On arriving in Shanghai in early 1936, Zhang received a hero’s welcome and was lauded by Chinese artistic luminaries. A Shanghai exhibition of Zhang’s work completed during his four years in Europe was attended by tens of thousands.

Then, with mentor Ma’s help, Zhang established Chongren Studio to teach his Chinese-infused Western-style art including painting, sculpture and photography.

The following year, the Sino-Japanese war began and Zhang was swept up in the chaos of the war years, followed by the tumultuous founding of the People’s Republic of China. Through it all, the apolitical Zhang kept up his prodigious output.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Zhang remained in China when the Communists assumed power, in 1949, creating works memorialising the founding of the New China and taking leading roles in cultural institutions such as the Shanghai Academy of Painting and Sculpture. He even taught a course on watercolour painting over the radio.

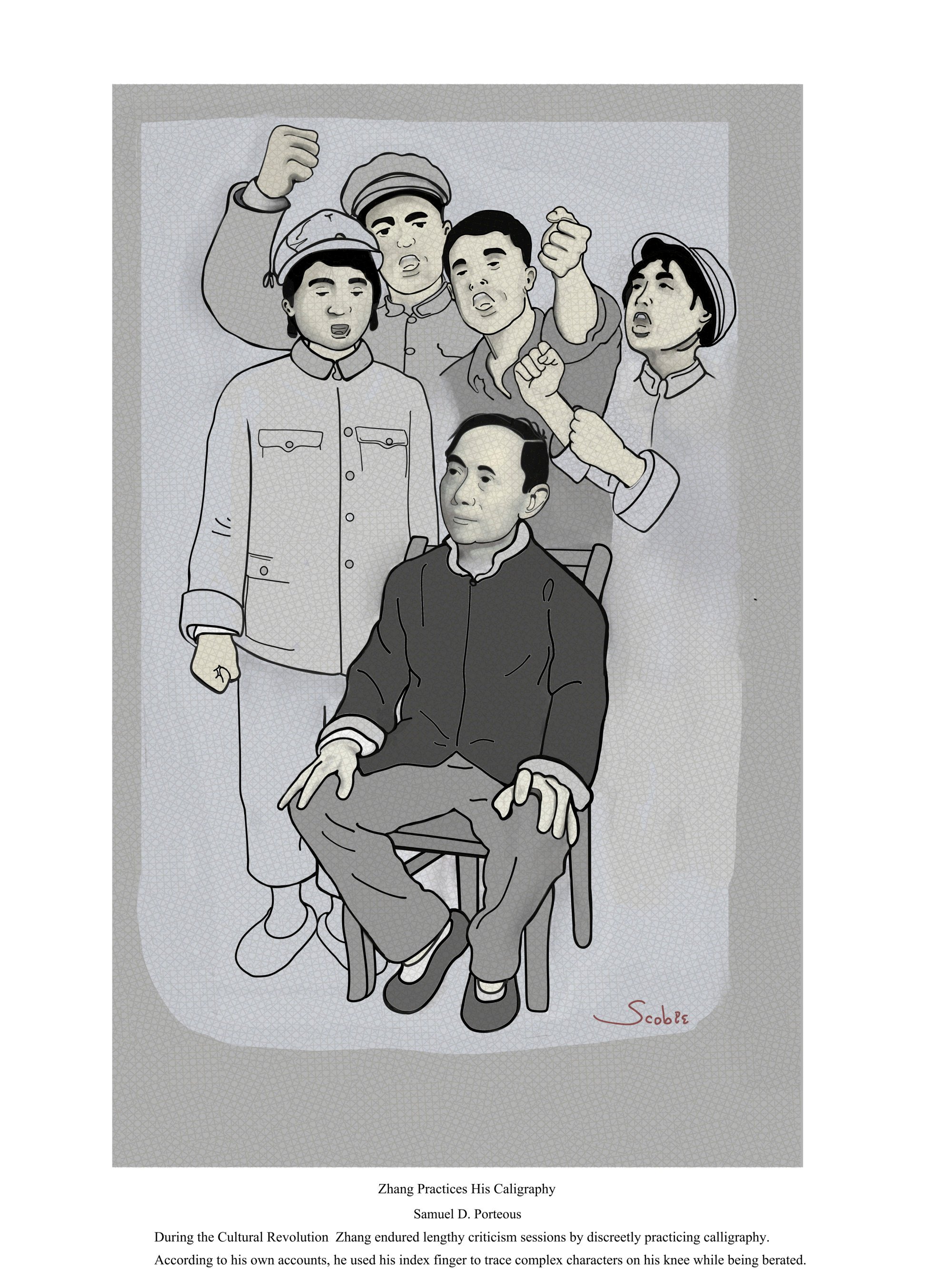

Zhang during the Cultural Revolution enduring the criticism sessions by discreetly practising his calligraphy while being berated. Illustration: Samuel Porteous

Then came the Cultural Revolution.

Zhang’s earlier works, including a 40cm-high (16-inch) model of a proposed statue of Chinese Nationalist politician Chiang Kai-shek on horseback, were used to brand him as a counter-revolutionary, guilty of separating art and politics.

The now over 60-year-old Zhang’s beloved home and studio of 30 years was seized and much of his work destroyed. He, his wife and their four children were consigned to a small room in his former home.

The ever resilient Zhang endured lengthy re-education sessions by discreetly practising calligraphy. According to his own accounts, he used his index finger to trace complex characters on his knee while being berated.

Meanwhile in Europe, the ever more heralded Hergé, having survived his own post-World War II tribulations regarding his work for a German-controlled newspaper during the occupation of Belgium, was now publishing his work out of a magazine he controlled.

Hergé welcomes his friend back to Belgium after 46 years apart. Photo: Getty Images

The moody Belgian was now almost as big a star as Tintin. A set of intensive interviews in the early 1970s delving into his influences, wherein he listed Zhang as perhaps his greatest artistic influence, recharged Hergé’s on-and-off interest in locating his old friend.

After years of failure, Hergé finally received news of Zhang in 1975, at a Chinese restaurant in Brussels. There while dining he met Wei Xubo, owner of the restaurant, Ming’s Garden. Wei turned out to be the son of a Chinese embassy official who had served in Belgium while Zhang studied there. Zhang had even attended Wei’s wedding.

Wei quickly contacted his father back in China who, with a little effort, soon provided Zhang’s contacts. Zhang’s son Xueren recalls his father was so excited when Hergé called that initially Zhang kept repeating “Hello! Hello!” in his beloved native Shanghai dialect, a language that Hergé, of course, could not understand.

The reconnection happily coincided with the end of the Cultural Revolution and Zhang’s return to a place of prominence in Chinese art circles. Hergé, however, was too ill to travel, and obtaining a visa for China was complicated by his belated 1973 acceptance of Madame Chiang’s invitation, which took him to Taiwan.

But in 1981, after years of effort, in which television journalist Gérard Valet, another big Tintin fan, played an essential role, Zhang obtained permission to travel to Belgium to give a series of lectures.

The visit kicked off with a reception at Brussels airport, described by Zhang biographer Jean-Michel Coblence as “worthy of a head of state”.

An ailing Hergé guaranteed he would greet Zhang at the airport, and he did. The tearful reunion more than 40 years in the making was broadcast across Europe.

After the initial euphoria, it became clear in the three months that followed – Hergé insisted Zhang stay at his home for the duration – that the two men were going in different directions.

While the PR people pushed the crowd-pleasing narrative that this was a real-life version of the joyful Tintin finds his missing friend Chang scenario of 1959’s Tintin in Tibet, behind the scenes something less rosy was going on. A frail but at-peace Hergé was suffering from the last stages of leukaemia, requiring at least one transfusion a week, living in his contemplative twilight.

He would die in 1983, but an active Zhang sensed his newly discovered notoriety in Europe offered the possibility of a new life in an environment more conducive to a sculptor than a fitfully opening China, where his preferred art form was a relative rarity.

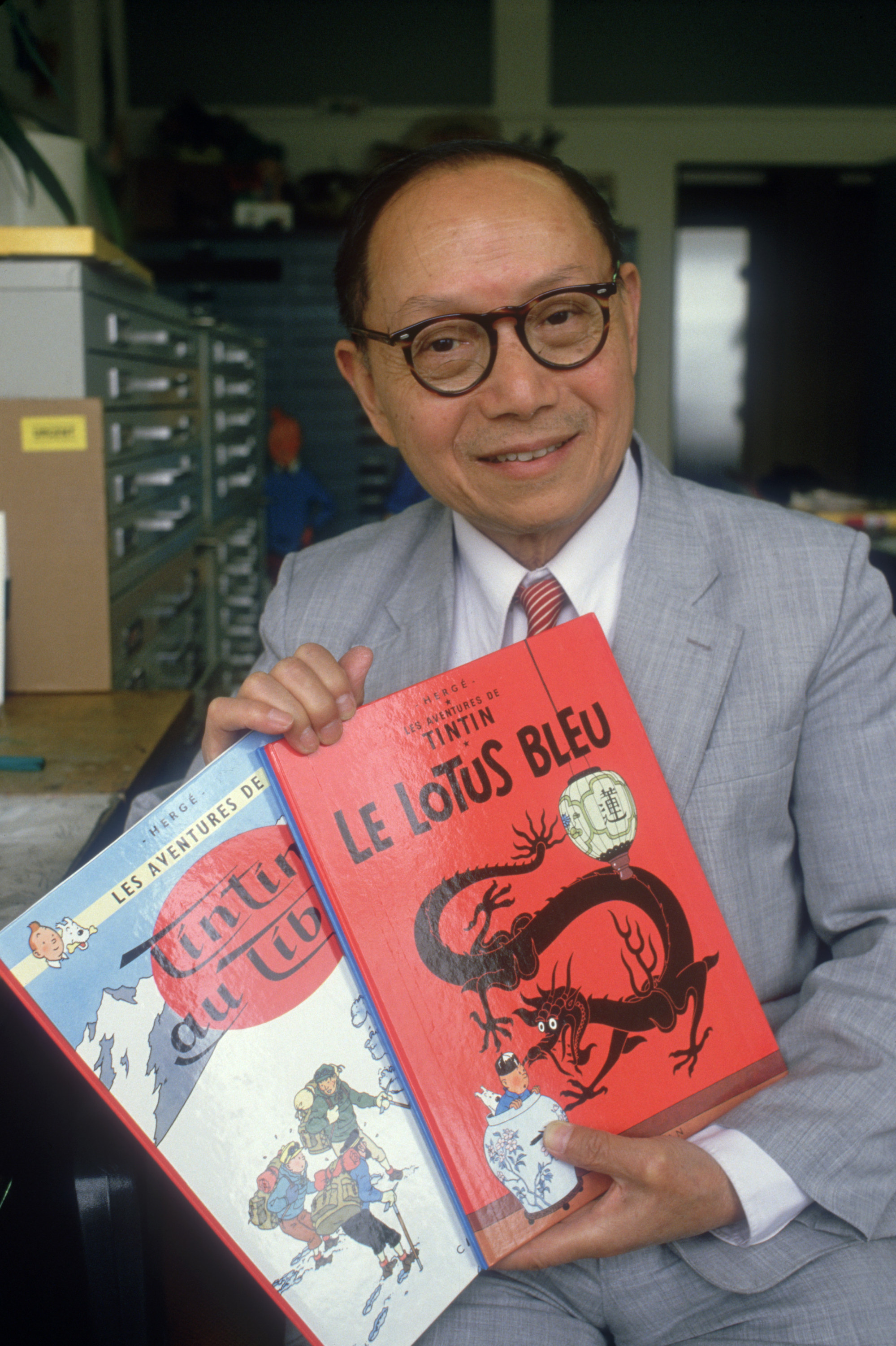

Zhang holds copies of The Blue Lotus and Tintin in Tibet. Photo: Getty Images

Zhang’s vision proved correct. In 1985, the larger-than-life French culture minister, Jack Lang, who adored Zhang’s work, invited the 78-year-old artist to France “to do something for Paris”.

This time, the still fiercely patriotic Zhang accepted the generous offer of a European citizenship and a studio. What followed was an autumnal renaissance for Zhang. A whirlwind of major commissions and lecture engagements, including sculptures of Hergé, and icons such as composer Claude Debussy and French president François Mitterrand.

To be sure, it was Zhang’s relationship with Hergé that triggered many of these opportunities, but it must also be recognised it was the old sculptor’s undeniable and often frustrated talent that allowed them to be realised.

During these years, interspersed with his work in France, Belgium and other parts of Europe, there were frequent returns to China to fulfil requests for sculptures there.

These included a bust of late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, finished when Zhang was 88 years old, and a masterful depiction of Zhang’s youthful acquaintance Nie Er, composer of the Chinese national anthem.

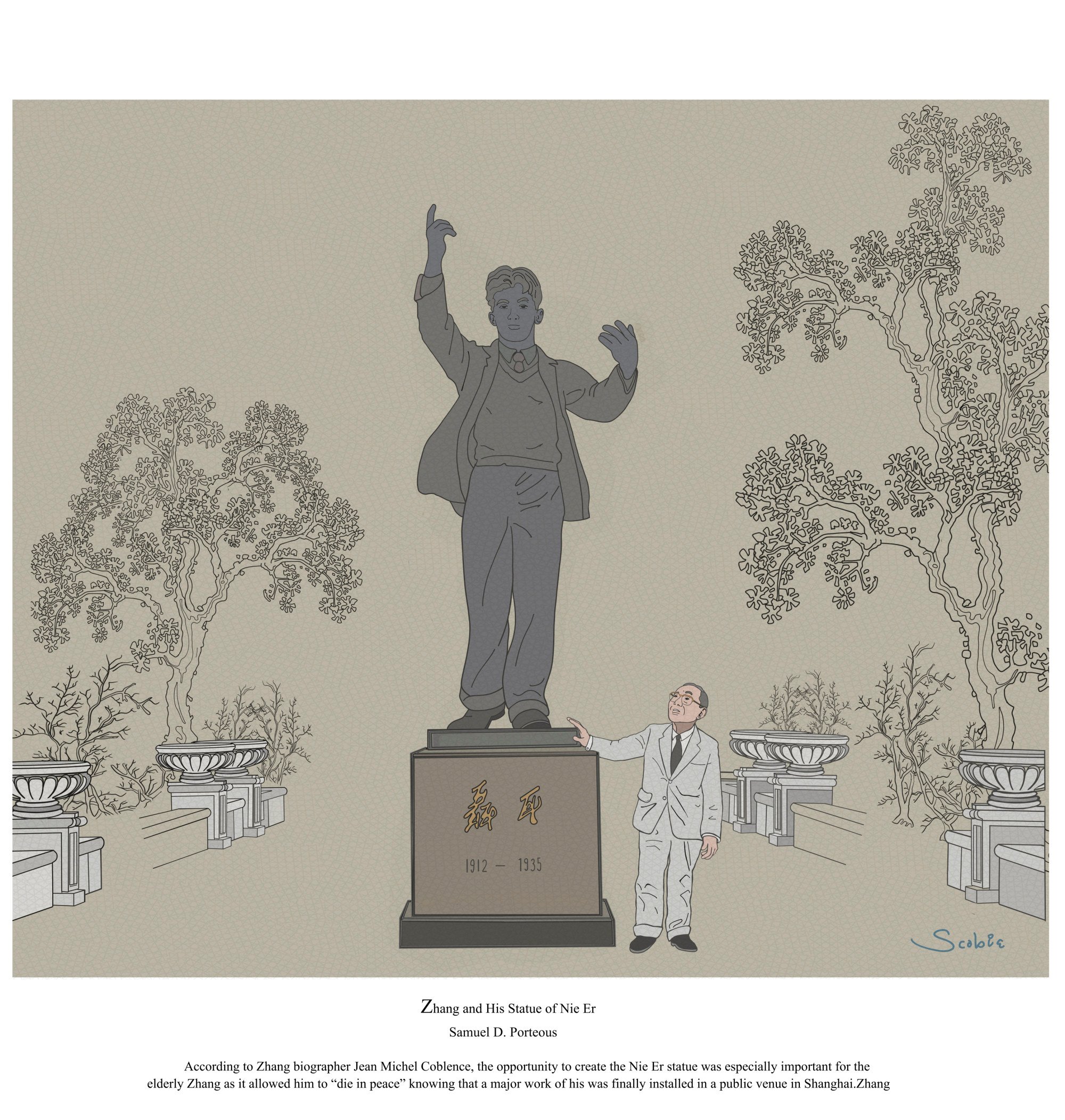

An elderly Zhang with the public statue of Nie Er. Illustration: Samuel Porteous

According to Coblence, the opportunity to create the Nie Er statue was especially important for Zhang, as it allowed him to “die in peace”, knowing that a major work of his was finally installed in a public venue in Shanghai.

It says something about the febrile nature of China’s current relationship with the West that a loopy theory emerged in 2018, postulating that the Zhang who returned to Europe in 1981 was an impostor sent by Chinese intelligence to infiltrate French high society.

Evidently the real thing, the invigorated Zhang finally slowed down, dying in France in 1998 aged 91. A museum dedicated to his life, including more than 100 original and replica sculptures and paintings – as well as detailing his role in producing The Blue Lotus – opened in 2003 in Zhang’s hometown of Qibao, in Shanghai, not far from what used to be the Tushanwan Orphanage.

According to Zhang’s daughter, Tchang Yifei, now working for Tintinimaginatio, the company that controls Hergé’s intellectual property, The Blue Lotus today is a source of pride in China, seen as a vigorous defence of the country’s culture when it needed it most.

More than 80,000 copies of The Blue Lotus and about 1.5 million volumes in total from the Tintin series are sold in China each year. The country’s first official Tintin store opened in Shanghai in 2003.